Confronting the Fable of St Thomas the Apostle’s Advent to India

When Christians in India are asked of their origin, or rather the advent of Christianity into India, they trace its origin to the mystical St Thomas the Apostle, one of the disciples of Jesus, and how he brought it to the Indian subcontinent.

The story goes as follows, with St Thomas arriving at Kerala’s Maliankara by sea. Tradition recounts that he established 7 famous churches, known as the Elarapallikal, at different places spread across the state.

He is also attributed to many miracles, with the most famous being the conversion of the Nambuthiris of Palayur. It is said that St Thomas observed the Nambuthiris performing their Sandhyavandhana, ritual oblations to Surya. On questioning them whether Surya would accept their offerings by keeping the water afloat, the Nambuthiris laughed at him, saying such a deed was impossible. To their shock, when St Thomas offered water, it floated up into the sky and transformed into a bunch of sparkling flowers.

This led to the conversion of said Nambuthiris into Christianity, with the Nasrani Christians of Kerala still claiming descent from the first Brahmins who were converted by St Thomas. In fact some of them even retained Hindu practices of wearing the Yajnopavitam and even observed Shuddhi rituals, a practice alien to Christianity.

Later on St Thomas is said to have travelled to the Coromandel Coast, specifically Thirumayilai, what is today known as Mylapore in Chennai. Here, it is said that he was canvassed by the local Brahmins to worship Devi Kali, and upon refusal, was killed by the King Mahadevan.

In reality, the episodes traditionally ascribed to St Thomas in India are largely legendary, with little to no foundation in credible history—or even within the Acts of Thomas, the very text often cited as their source. Despite this, the narrative has been perpetuated with remarkable persistence, frequently echoed in popular media and even academic discourse, despite the absence of supporting historical, textual, or archaeological evidence.

And this is where the fable begins to unravel. When we peel back the layers of folklore and compare them against contemporary records, early Christian texts, and archaeological evidence, we find gaping silences where one would expect confirmation. The Acts of Thomas itself, the supposed cornerstone of this tradition, places the Apostle in a very different geography altogether, while early Church Fathers—remarkably meticulous in chronicling apostolic missions—make no mention of his presence in India. What we are left with, then, is a tale stitched together centuries later, retrofitted to give Christianity in India an ancient and “native” origin. But how did this narrative take shape, and why has it endured so powerfully in the collective memory? That is the question we must now confront.

The Christian Take on the Acts of Thomas

As discussed earlier, the source for the current narration of St Thomas’ journeys in India is the apocryphal text of the Acts of Thomas, an account reputed to be from the 3rd century CE.

The text begins with Jesus tasking Thomas to spread his word to the land of India. But when Thomas proves reluctant, Jesus sells him into the slavery of a merchant by name Abban, who is from the kingdom of the Indian king Gundaphorus.

Thomas promises to build the king a grand palace, in line with his supposed talents as a carpenter. However, when the king’s soldiers report to him that Thomas has started no work whatsoever on a palace but has instead been distributing the wealth allotted for constructing the palace to the poor and sick.

The king, furious, imprisons both Abban and Thomas for deception. But then his brother Gad dies, and journeys to heaven, where he sees that Thomas has indeed built a grand palace for the king. He returns to the land of the living to tell Gundaphorus of this, hearing of which both the king and his brother convert to Christianity.

The Acts continue with Thomas performing many miracles, resurrecting a boy who dies of snakebite, expelling evil demons and helping an accursed young convert who murdered a woman. It ends with Thomas being put to death by a king named Misdaeus, who however regrets the act and also converts.

Now, there are two interesting points to note here.

The first is that there are little to no parallels between the traditional retelling of the story in India, and the Acts of Thomas themselves, on which these accounts are supposedly based.

While Thomas is put to death by Misdaeus for converting his wife to Christianity, nowhere does it mention that he was commanded to the worship of Kali or any other Hindu gods, and was killed on refusal.

Nor is there any mention of the famous incident of the conversion of the Brahmins of Palayur. Surely an incident as notable as holding water suspended mid-air and converting into “sparkling flowers” would be recorded by Thomas as a noteworthy achievement?

The second and more interesting observation is that even the original Acts of Thomas is deemed heretical by the Roman Catholic Church.

In the Decretum Gelasianum, a papal decree attributed to Pope Gelasius I, the same is explicitly stated as follows :

“THE REMAINING WRITINGS which have been compiled or been recognised by heretics or schismatics the Catholic and Apostolic Roman Church does not in any way receive; of these we have thought it right to cite below a few which have been handed down and which are to be avoided by Catholics: … the Acts in the name of the apostle Thomas apocryphal …”

So even if we do accept that the Indian narration of the story of Thomas is based on the Acts of Thomas, how can a story that is outright rejected by the Catholic Church itself still be propagated in Bharat?

Modern scholarship unanimously rejects the Acts of Thomas as historical fiction. Key problems include:

- Anachronistic elements: The text describes events impossible for the 1st century CE context

- Late composition: Written 200+ years after the alleged events

- Gnostic influences: Contains theological elements foreign to apostolic Christianity

- Geographical confusion: Conflates different regions and kingdoms

The text likely reflects 3rd-century Syrian Christianity projected backward onto an apostolic figure rather than preserving genuine historical traditions about Thomas. While it provides valuable insights into early Christian ascetic movements and missionary ideologies, it offers no reliable information about actual 1st-century Christian activity in India.

This has been the unanimous stance of Western Christian historians with respect to the legend of Thomas.

The Modern Day Santhome Basilica

Going back to the story of St Thomas’ martyrdom, it is commonly believed that he was killed in what is today Mylapore in Chennai. As discussed earlier it is believed that he was sentenced to death by King Mahadevan for refusing to worship Devi Kali.

In the 16th century, the Portuguese claimed to have discovered the tomb of St Thomas, somehow pristinely intact for over almost one and a half millenia. Tradition recounts that they were the first to build a small church at the location of his tomb. This modest church was further expanded when Mylapore became a Portuguese diocese in the 17th century.

Later on, the British in the 1890s built what is today the Santhome Basilica, under the watchful eyes of Henry Joseph Reed Da Silva, Bishop of Mylapore. It was recognised as a Basilica in 1956 by Pope Pius XII, and is today a destination for Christians both within and outside of India. It is also said to be one of only 3 basilicas spread out across the entire globe

The Basilica also ensconces the tomb of St Thomas, which visitors can still observe.

It is quite interesting that while the story of St Thomas notes that he was persecuted and killed by the local ruler or chieftain, somehow he allowed for his body to be preserved well, so well that the Portuguese were still able to discern that this was the exact tomb of St Thomas and build a church over it.

Why would the same King Mahadevan who ordered for the death of St Thomas over his refusal to follow Hindu customs, allow for his body to be buried in Christian fashion rather than burning it as was Hindu custom?

And that is not the only evidence questioning the popular narrative surrounding the Santhome Basilica being St Thomas’ resting place.

The Destruction of The Kapaleeshwarar Temple

The Kapaleeshwarar temple today stands as the epicenter of Mylapore, commonly known as Thirumaiyilai and Mayurapuri throughout the ages.

It is perhaps the oldest locality of what is modern day Chennai, with the other claimant being Thiruvallikeni. Referenced in Sangam-era literature and in the works of the Azhvars and Nayanmars, it forms a major part of the history of Chennai.

The Greek geographer Claudius Ptolemy mentions Millarpha, a port city of the Coromandel Coast, in his Geographia. This city is universally identified as what is modern day Mylapore. The Geographia was composed circa 140 CE.

Although there is significant evidence to prove that the temple existed from at least the 7th century CE, and perhaps even existed during the Sangam era, archaeological surveys conducted on the modern temple complex show that it is most probably a Vijayanagara-era construction dated to the 16th to 17th century CE.

Another interesting aspect is that the poems of the Nayanmars and Arunagirinathar, a saint dedicated to the worship of Murugan, place the Kapaleeswarar temple to a completely different geographical location.

The current Kapaleeshwarar temple is completely inland, with the Marina Beach coast being more than a kilometre away from the main temple complex.

However in the hymns of Thirugnana Sambandar and Arunagiri, the temple is described as being situated coastally, on what is today the Marina beachfront.

மட்டு இட்ட புன்னைஅம்கானல் மடமயிலைக்

கட்டு இட்டம் கொண்டான், கபாலீச்சுரம் அமர்ந்தான்,

ஒட்டிட்ட பண்பின் உருத்திரபல்கணத்தார்க்கு

அட்டு இட்டல் காணாதே போதியோ? பூம்பாவாய்! (1)

- Tirumurai 2. 47- Mattita Punnaiyam

“In the beautiful Mayilai which has sea-shore gardens of punnai (mast-wood) trees that pour with nectar, in which Lord Siva resides with desire in Kapaleeswaram delights. The Rudras along with various groups of Ganas in human form, (i.e., the devoted pilgrims) who come there are served food (prasada) – do you go without seeing this wonderful sight, O Poompavay!”

Note “sea-shore gardens of Punnai”. The poem specifically notes that the Kapaleeshwarar temple contained sea-shore groves of the Punnai tree.

But the current Kapaleeshwarar temple is completely inland. So how could it have sea-shore groves of the Punnai tree, within or nearby the current temple complex?

Sambandar proceeds to sing the following as well :

ஊர் திரை வேலை உலாவும் உயர் மயிலைக்

கூர்தரு வேல் வல்லார் கொற்றம் கொள் சேரிதனில்,

கார் தரு சோலைக் கபாலீச்சுரம் அமர்ந்தான்

ஆர்திரைநாள் காணாதே போதியோ? பூம்பாவாய்!

“Where the rolling waves lap the shores of the great Mayilai whose lanes are full of brave warriors, experts at wielding sharp lances and whose dense groves bring rain clouds – do you go without seeing the special Ārtira festival, O Poompavay!”

மடல் ஆர்ந்த தெங்கின் மயிலையார் மாசிக்

கடல்ஆட்டுக் கண்டான், கபாலீச்சுரம் அமர்ந்தான்,

அடல் ஆன்ஏறு ஊரும் அடிகள், அடி பரவி,

நடம்ஆடல் காணாதே போதியோ? பூம்பாவாய்!

“In Mayilai where there are coconut glades with broad swaying fronds, during Māci festival, the Lord witnesses the throngs of devotees bathing in the sea, dancing in worship of the lotus feet of Siva who rides the ferocious bull – do you go without seeing the devotees’ seaside activities, O Poompavay!”

From the above verses, it is clear that the original Kapaleeshwarar temple was situated on the seashore and not inland as it is today.

This sentiment is only reinforced by Arunagirinathar, the great devotee of Murugan, in the following verses : “கயிலைப் பதியரன் முருகோனே

கடலக்கரைதிரை அருகே - சூழ்ம

யிலைப் பதிதனில் உறைவோனே

மகிமைக் கடியவர் பெருமாளே!”

O Muruga, the one who resides on the sacred hill of Kailai,

Near the edge of the ocean waves, surrounded by its embrace,

Who dwells in the holy city of Mayilai and rests therein,

O great Lord, mighty in glory and majesty!

From the above we can say with certainty that the original venue of the Kapaleeshwarar temple was on the beachfront of Mylapore, rather than its inland location today.

This leads to two questions.

- What was the original venue of the Kapaleeshwarar Temple before its “shifting” in the Vijayanagara era?

- How does this tie in with the legend of St Thomas and the Santhome Basilica?

Both of these questions are not distinct but rather innately entwined, and have a singular answer.

Archaeological investigations at the Santhome Basilica site have yielded substantial evidence of an original Hindu temple complex. Excavations conducted by the Archaeological Survey of India in 1923 uncovered remains including pillars, inscriptions, and sculptures. These discoveries included inscriptions by Vikrama Chola , confirming the site's significance in the Chola period.

The inscriptional evidence includes references to both Hindu and Jain religious structures at the site. A fragmentary inscription from the 12th century Chola period found in the San Thome Church refers to a Jain temple dedicated to Neminathaswami. This indicates the religious diversity of the area before Portuguese colonization.

When sea erosion occurred near the end of the 19th century, causing a landslip on the San Thome beach, it revealed "carved stone pillars and broken stones of mandapam found only in Hindu temples". These discoveries provided physical confirmation of the temple complex that once occupied the coastal site.

Additional evidence comes from the bishop's palace compound on the south side of San Thome Cathedral, which "still contains scattered temple ruins and includes a museum". V.R. Ramachandra Dikshitar, a famous Indologist, noted that the great Shiva temple covered the area now occupied by this Basilica, with various temple artifacts still visible in the compound.

N. Murugesa Mudaliar, in Arulmigu Kapaleeswarar Temple Mylapore,writes, “Mylapore fell into the hands of the Portuguese in 1566, when the temple suffered demolition. The present temple was rebuilt around three hundred years ago. There are some fragmentary inscriptions from the old temple still found in the St. Thomas Cathedral.”

P.K. Nambiar, in Census of India 1961, Vol. IX, Part XI, writes “It is a historical fact that the Portuguese, who visited India in the 16th century, had one of their earliest settlements at San Thome, Mylapore. In those days they were very cruel and had iconoclastic tendencies. They razed some Hindu temples to the ground. It is probable that the Mylapore temple referred to in the Thevaram hymns was built on the seashore and that it was destroyed by the Portuguese about the beginning of the 16th century.”

Prominent archaeologist Dr. R. Nagaswamy, former Director of Archaeology Tamil Nadu, personally attested to the destruction and looting, and confirmed the presence of Chola-era temple inscriptions within the Santhome Cathedral and Bishop’s House.

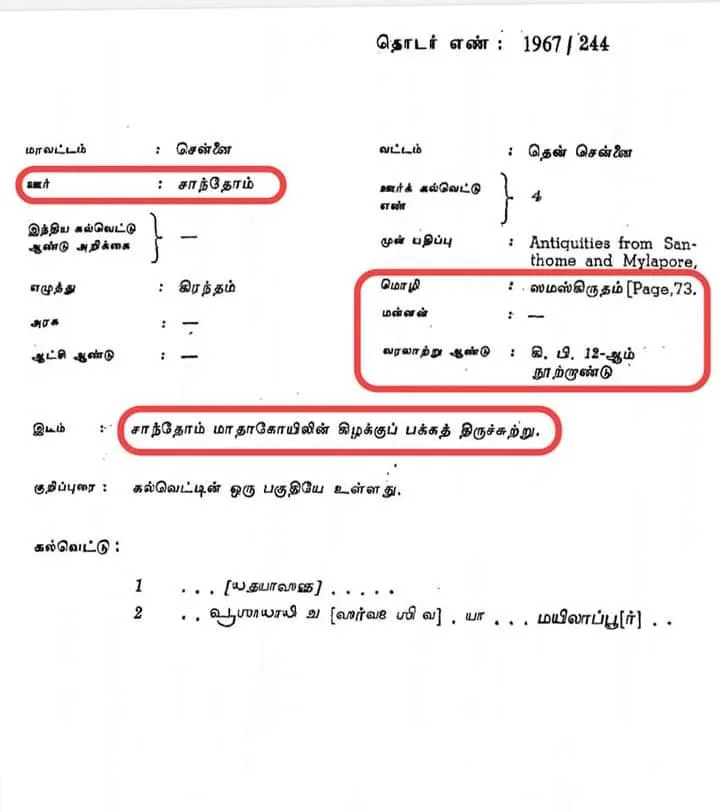

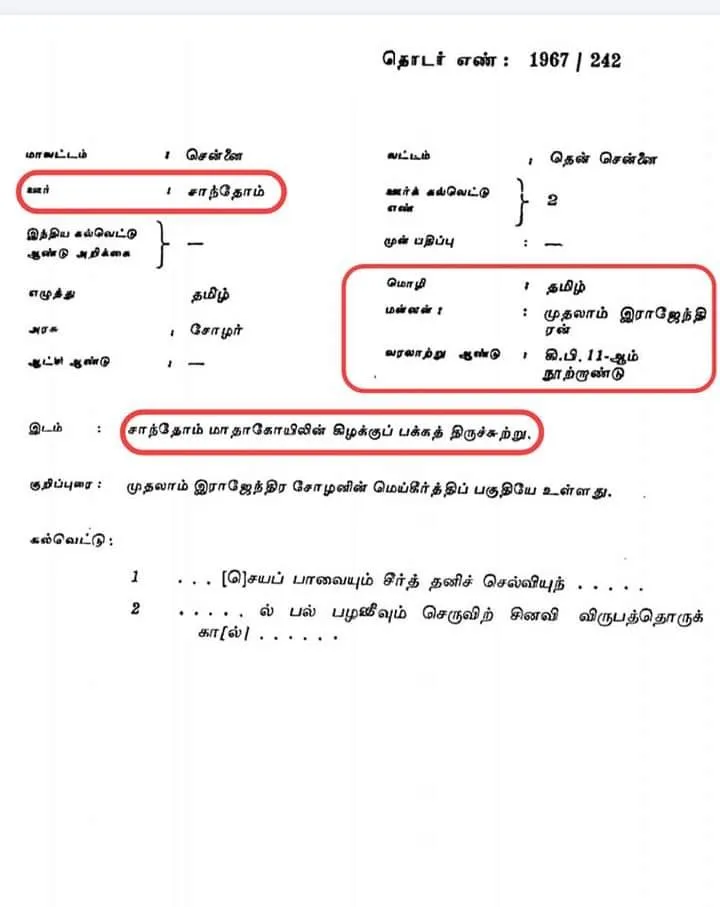

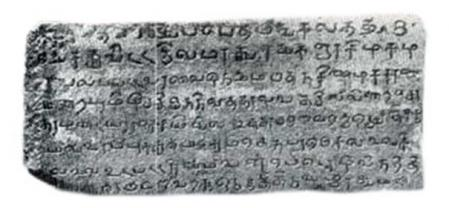

Affixed are transcriptions of the inscriptions found in and around the Basilica :

It is also notable that the Tamil magazine Dinamalar, which was for a long time propagating the myth of St Thomas in Thirumayilai, in 2012, admitted that shattered fragments of stone inscriptions from the original Kapaleeshwarar temple are still to be found in the precincts of the Santhome Basilica.

And here are some of the fragments that, luckily, were recovered from the Basilica grounds :

The above is an inscription from the 12th century belonging to Vikrama Chola. It records a grant of tax-free land for lighting lamps at night for Lord Nataraja. This inscription was once lying in the veranda of the church, and was later discovered by the Department of Archaeology.

To quote Ishwar Sharan, Canadian author better known as Devananda Saraswati,

“The Portuguese were familiar with the St. Thomas legend long before they arrived in India. They knew Marco Polo’s Il Milione, made popular in Europe in the fourteenth century, and the earlier sixth century Latin romances De Miraculis Thomae and Passio Thomae…The Passio Thomae had St. Thomas killed by a Pagan priest with a sword, and De Miraculis Thomae had him killed by a Pagan priest with a lance. These stories were at odds with the one found in the Acts of Thomas, which had the apostle executed on the orders of a Persian king, by four royal soldiers with spears.”

“The Portuguese preferred the Pagan-priest-with-a-lance story found in De Miraculis Thomae. They added Marco Polo’s seaside tomb to it, and elements from Syrian Christian traditions that they had gathered in Malabar, and concocted a legend…”

And today, we have the story of St Thomas, the innocent Apostle of Christ who was killed by Brahmins for refusing to adhere to the Hindu faith.

When in fact, the reality was that the Portuguese invaders had brutally destroyed a local temple and in all probability, looted its wealth to fund the construction of the Basilica over its very remains.

To quote Belgian author Konraad Elst,

“No one knows how many Hindu priests and worshipers were killed when the Christian soldiers came to remove the curse of Paganism from the Mylapore beach. Hinduism does not practice martyr-mongering, but if at all we have to speak of martyrs in this context, the title goes to the Shiva-worshipers and not to the apostle Thomas.”

Now a question invariably arises : What was the purpose of concocting such an elaborate story, and concealing it so? How did it benefit the Portuguese in any way?

The truth is that it did not benefit the Portuguese, but rather their masters, the Catholic Church, in their timeless quest of converting the rest of the “pagan” world into the path of Christ.

To quote Sitaram Goel,

“Firstly, it is one thing for some Christian refugees to come to a country and build some churches, and quite another for an apostle of Jesus Christ himself to appear in flesh and blood for spreading the Good News. If it can be established that Christianity is as ancient in India as the prevailing forms of Hinduism, no one can nail it as an imported creed brought in by Western imperialism.

Secondly, the Catholic Church in India stands badly in need of a spectacular martyr of its own. Unfortunately for it, St. Francis Xavier died a natural death and that, too, in a distant place. Hindus, too, have persistently refused to oblige the Church in this respect in spite of all provocations. The Church has had to use its own resources and churn out something. St. Thomas, about whom nobody knows anything, offers a ready-made martyr.

Thirdly, the Catholic Church can malign the Brahmins more confidently. Brahmins have been the main target of its attack from the very beginning. Now it can be shown that the Brahmins have always been a vicious brood, so much so that they would not stop from murdering a holy man who was only telling God’s own truth to a tormented people. At the same time, the religion of the Brahmins can be held responsible for their depravity.

Fourthly, the Catholics in India need no longer feel uncomfortable when faced with historical evidence about their Church’s close cooperation with the Portuguese pirates in committing abominable crimes against the Indian people. The commencement of the Church can be disentangled from the advent of the Portuguese by dating the Church to a distant past. The Church was here long before the Portuguese arrived. It was a mere coincidence that the Portuguese also called themselves Catholics. Guilt by association is groundless.

Lastly, it is quite within the ken of Catholic theology to claim that a land which has been honoured by the visit of an apostle has become the patrimony of the Catholic Church. India might have been a Hindu homeland from times immemorial. But since that auspicious moment when St. Thomas stepped on her soil, the Hindu claim stands cancelled. The country has belonged to the Catholic Church from the first century onwards, no matter how long the Church takes to conquer it completely for Christ.”

Conclusion :

Confronting the fable of St Thomas the Apostle's advent to India demands a careful disentangling of legend from historical fact. The enduring narrative—of the apostle’s miraculous journey, conversions, and martyrdom—owes more to late traditions, colonial myth-making, and institutional needs than to contemporary documentation, archaeological evidence, or even the very apocryphal texts cited as its foundation.

Despite the reverence with which Indian Christians recount Thomas’s supposed arrival at Kerala’s Maliankara and his establishment of the Elarapallikal churches, modern scholarship and the testimony of early Christian writers offer little to corroborate these stories. The famous miracle of the water at Palayur, the mass conversion of Brahmins, and his violent end at Mylapore are absent in the Acts of Thomas—leaving only centuries-later local oral traditions and the strategic elaborations of Portuguese colonial and Catholic interests.

Archaeological assessment of Mylapore and the Kapaleeshwarar temple site reveals a very different history: one of medieval and Chola-era temple tradition, Portuguese destruction, and tangible evidence of Hindu presence, rather than a pristine apostolic tomb. The transplantation of the coastal temple inland, referenced in centuries-old Tamil devotional poetry, further contradicts the narrative now enshrined at the Santhome Basilica.

The persistence of this fable can be traced to its deep utility for colonial and ecclesiastical actors. By retrofitting Christianity into India’s ancient fabric, and recasting Brahmins as perennial antagonists, the Church could claim both antiquity and authority—bolstering its legitimacy, erasing colonial guilt, and asserting a spiritual patrimony stretching to apostolic times. The myth thereby served not only faith but also political and ideological purposes.

In the end, the story of St Thomas’s Indian mission stands as a striking example of how legend can be weaponized—reshaping memory, appropriating history, and masking inconvenient truths about conquest and cultural erasure. To honor genuine history, one must look past the layers of narrative accretion to the silent testimony of early records, archaeological findings, and the ancient Tamil literary landscape. The truth is not that Christianity in India was born from apostolic footsteps, but from the interactions, migrations, and sometimes, the violence and destruction of later ages.

Let us call the legend what it is: a monumental fable, remarkable for its persistence, but ultimately unsupported by history. Only by confronting and deconstructing such myths can we render justice both to the memory of ancient Tamil heritage and to the complexity of India’s religious past.

Sources :

- The story of St Thomas in India : https://www.anglicanfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/Saint-Thomas-Paper.pdf

- The Acts of Thomas : https://www.nasscal.com/e-clavis-christian-apocrypha/acts-of-thomas/

- History of the Santhome Basilica : https://catholicchurches.in/directory/chennai-churches/basilica-of-santhome-cathedral-santhome-mylapore.htm?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- Decretum Gelasianum : https://www.tertullian.org/decretum_eng.htm?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- The Namboothiri Connection of St Thomas : https://ijrpr.com/uploads/V5ISSUE11/IJRPR34676.pdf

- Arrival of St Thomas in India : ARRIVAL OF ST. THOMAS IN INDIA AND HIS MISSIONS: HISTORIOGRAPHICAL APPROACH K.S.Mathew

- Ishwar Saran’s observations on the story of St Thomas and the Kapaleeshwarar Temple : https://ishwarsharan.com/the-myth-of-saint-thomas-and-the-mylapore-shiva-temple/exploding-a-mischievous-myth-sita-ram-goel/

- History of the Kapaleeshwarar Temple : https://dome.mit.edu/handle/1721.3/180565

- The Portuguese Demolition of the Kapaleeshwarar Temple : https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Kapaleeshwarar_Temple

- The Myth of Saint Thomas and the Mylapore Shiva Temple : https://archive.org/details/isbn9789385485206/page/39/mode/2up?view=theater

- Mylapore Kapaleeshwarar was once situated on the Beach (Santhome Church) : https://thamilkalanjiyam.blogspot.com/2018/07/blog-post_18.html?m=1

- Dinamalar’s Sudden Historical Investigation on Kapaleeswarar: The Real Temple Was on the Seashore : https://thomasmyth.wordpress.com/2012/04/06/original-kapaleswarar-temple-inscriptions-found-disappeared-mutilated/