Decolonizing the Swastika: Western Academia’s Role in a Global Misrepresentation

Whenever we think of Nazi Germany, there are two things that immediately spring to mind - a failed painter from Austria and another symbol that defined the Third Reich - a hooked cross, better known as the Hakenkreuz.

But the modern world has a different name for this symbol - an odd name considering its nature and Hitler’s views on the culture from which this name arose.

Nobody today recognises the name “Hakenkreuz”. Yet when we use the word Swastika, we are immediately reminded of Nazi persecution and the horrors of the Holocaust, with mere mentions of the word being equated with anti-Semitism and fascism.

What if I told you that the Nazis themselves never referred to their symbol as the Swastika, but unanimously called it the Hakenkreuz, or the hooked cross, an important symbol in early Christian theology? And that the misappropriation of the word Swastika, is an open attempt by Western academia to divert hate for adopted Christian symbolism towards Dharmic faiths as a whole?

Read on to find out more about the true origins of the Swastika, its fundamental difference from the Hakenkreuz and how Western historians engineered one of the greatest rug-pulls in the study of modern history.

Origins of the Swastika

The oldest known examples of the Swastika are from the IVC, believed to be from around 2700 BCE. It also occurs in the Mesopotamian and Cretan civilizations later on, circa 2500 BCE and 2000 BCE respectively.

The ordinary Swastika is an equilateral cross whose arms are bent at right angles - It can be portrayed clockwise/right facing or counter clockwise/left facing.

The origin of the word itself is linked to the Sanskrit term स्वस्ति।(Swasti), denoting auspiciousness. The term first appears in the Rig Veda in mantras seeking benediction from the Devatas.

Therefore, the word Swastika can be roughly translated to mean a symbol of auspiciousness. In Hinduism, the right-facing swastika denotes the sun (Surya), prosperity, and good luck, while the left-facing swastika relates to tantric and nocturnal powers. Jain and Buddhist traditions also integrated these symbols in ritual and architecture, emphasizing their auspicious, non-violent connotations.

The Swastika is also mentioned in the Harivamsa Parva of the Mahabharatha, as an insignia of some kings of Bharathavarsha.

With the transmission of Buddhism the character and motif entered China, Korea, Japan and Southeast Asia, where it often became associated with Buddhism, longevity and good fortune. In East Asian visual culture it is sometimes conflated with the Chinese character wàn as an auspicious sign.

Now, one might ask - how did this innocuous symbol of prosperity end up on the flags of a genocidal regime in the West?

The Gammadion and its significance in Christian Theology

As mentioned earlier, crude forms of what was known in Indic civilization as the Swastika were found in the Cretan civilization and dated to around 2000 BCE. Similar symbols were also recovered in an excavation of Troy in 1871 by noted archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann.

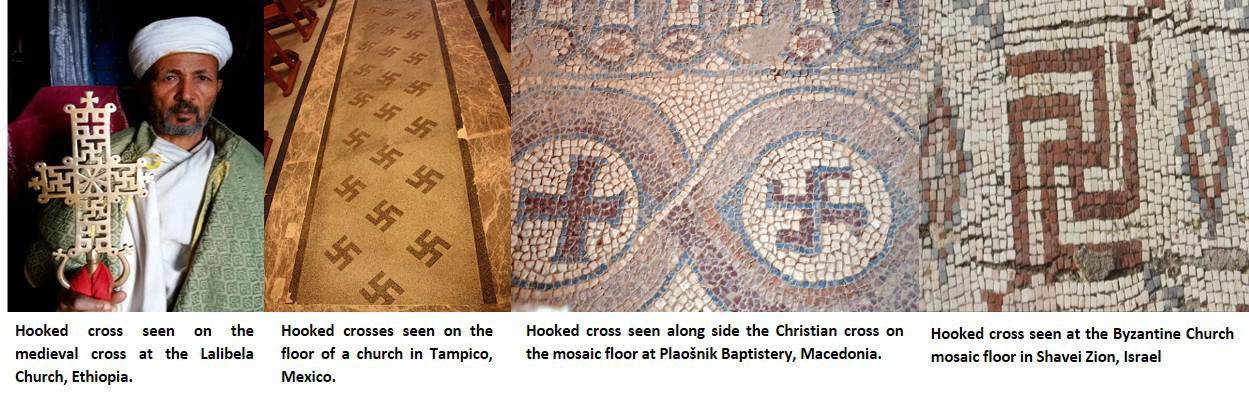

By the time of the Byzantines, the symbol came to be known as the Gammadion cross, Crux Gammata, and remained prevalent throughout early Christian and Byzantine art wherein it held profound theological significance.

The gammadion was constructed from four Greek capital gamma letters (Γ) joined at a common base, forming a hooked cross pattern.

Early Christians employed this symbol extensively:

- Funerary Art: The gammadion appeared on early Christian tombs and catacombs, where it served as a veiled symbol of the cross during periods of persecution.

- Sacred Vestments: It adorned the garments of priestly figures, including the fossores (gravediggers) and even decorated the tunic of the Good Shepherd in early Christian iconography.

- Architectural Elements: The symbol featured prominently in Byzantine churches, including the famous mosaics of Ravenna's Basilica of San Vitale from the 6th century.

- Medieval Churches: Throughout medieval Europe, the hooked cross appeared in church decorations, coats of arms, and textile fragments from as early as the 12th century.

It also held immense theological significance for Christianity. Early Christians were fearful of using the cross itself as it would invite persecution from the Romans, and hence adopted the Crux Gammata as a symbol of Christ’s resurrection on the cross.

Early Christian art often emphasised the cross not only as an instrument of death but as a symbol of Christ’s victory over sin and death. For example, the Crux Gammata appears in art to represent the cross in triumph.

The gammadion form appears in tomb-inscriptions and catacomb paintings (in places where Christians buried their dead),symbolising resurrection and eternal life, associated with Jesus.

It was this Crux Gammata that was adopted by Hitler as the symbol of Nazi Germany - not the Hindu, Indic Swastika as is often portrayed by Western historians.

The Nazi Adoption of the Gammadion and its Evolution into the Hakenkreuz

The Crux Gammata featured prominently in the iconography of Austria’s Lambach Abbey - the same institution where Adolf Hitler was a choirboy in his childhood.

It was installed by then Abbot Theodorich Hagn, a Benedictine monk who oversaw the institution from 1866 to 1887.

Hitler’s deep connection to the Church and Christianity is well known - in fact it was the Cistercian monk Jörg Lanz von Liebenfels, an outspoken racial theorist who played a heavy influence on Hitler’s political thought and ideas of racial purity. In fact the Catholic Church was one of the first institutions to legitimize Hitler’s rise to Chancellor through the Reichskonkordat - a concordance between the Vatican and the Reich.

Werner Maser, a leading German historian discovered in Hitler's early notebooks "a sketch of a projected book cover featuring the hooked cross which looked similar to what would become the Nazi flag of the future". Maser wrote that "the hooked cross and the banner reflected the influence of the Hakenkreuz that Hitler saw at Lambach Abbey and on the coat of arms of Abbot Hagen".

Robert Payne, Hitler's prominent biographer, concluded in The Life and Death of Adolf Hitler (1973):

"Abbot Theoderich Von Hagen's Hakenkreuz was probably the ancestor of the Nazi Hakenkreuz."

Payne noted that Hitler had "mentioned his fascination with the [monastery's] abbot—as a future ideal for himself," and that the Abbot's hooked cross symbol left a lasting impression on the young Hitler.

Daniel Rancour-Laferriere, author of The Sign of the Cross: From Golgotha to Genocide, said the following :

"Hitler's decision to use the Hakenkreuz as a symbol of the Nazi party may have been due to his childhood upbringing at the Benedictine Monastery in Austria, where he repeatedly saw the 'hooked cross' in multiple places."

Rancour-Laferriere emphasized: "It cannot be disputed that, as a boy, Adolf Hitler repeatedly saw the hooked cross in the Christian context of the Benedictine Catholic Monastery where he had his choir lessons and other classes."

It is important to note that Nazi leaders or officials, including Hitler, never referred to their official symbol as the Swastika, and always used the word Hakenkreuz whenever they alluded to it.

To quote Hitler himself, as he recounted in Mein Kampf :

"I myself, meanwhile, after innumerable attempts, had laid down a final form; a flag with a red background, a white disk, and a black Hakenkreuz in the middle. After long trials I also found a definite proportion between the size of the flag and the size of the white disk, as well as the shape and thickness of the Hakenkreuz."

Hitler explicitly explained his symbolism:

"In red we see the social idea of the movement, in white the nationalistic idea, in the Hakenkreuz the mission of the struggle for the victory of the Aryan man."

Hitler explicitly connected the Hakenkreuz to Christian anti-Jewish theology. In a speech in Munich on October 25, 1930, Hitler called the Hakenkreuz "a part of the Christian tradition" and "a symbol of the struggle against Jews, Marxists, and Bolsheviks".

Hitler's worldview, as expressed in Mein Kampf and various speeches, portrayed Jesus as an "Aryan fighter" persecuted by Jews:

"And the founder of Christianity made no secret indeed of his estimation of the Jewish people. When He found it necessary, He drove those enemies of the human race out of the Temple of God... But at that time Christ was nailed to the Cross for his attitude towards the Jews…"

The evidence overwhelmingly demonstrates that the Nazi Hakenkreuz originated from Christian ecclesiastical symbolism—the gammadion cross—rather than from Hindu or Eastern traditions.

But how did all this monumental evidence get ignored in favour of a shortsighted and ill-researched terming of the Nazi Hakenkreuz as the Swastika?

Western Academia’s role in hiding the history of the Hakenkreuz

Interestingly, the original 1933 English translation by Edgar Dugdale correctly rendered the Nazi symbol as "hook-cross" or "hooked-cross," maintaining the distinction from the swastika. However, every subsequent major English translation after Dugdale's version deliberately mistranslated "Hakenkreuz" as "swastika," despite it being semantically incorrect and contextually misleading.

To quote Rev. T.K. Nakagaki, author of The Buddhist Swastika and Hitler's Cross, "Whether intentional or not, these translators protected the Christian cross and damaged the Eastern religious swastika".

Even The Times newspaper did not use the word "swastika" to refer to the Nazi symbol until 1932-1933, and even afterwards used it very sparingly.

Historian Robert P. Ericksen, author of “Theologians Under Hitler and German Churches and the Nazis”, documents how Western academia systematically avoided confronting Christian institutional complicity. Ericksen notes that when he published his first book in 1985 focusing on three prominent German Christian theologians' embrace of Nazi ideology, reviewers were deeply uncomfortable with the implication that Christian complicity was not aberrational but widespread.

The problem was institutional: For approximately 30 years after 1945, most Western historians deliberately accepted and promoted a mythology that deflected attention away from Christian antisemitism and toward narrow circles of Nazi Party leaders and SS functionaries.

As Ericksen observed:

"For several decades it was widely assumed that churches had been special victims of the Nazi state and that Christians had been natural opponents of the Nazi regime.”

This, as we will note, is obviously false.

When Christopher Browning conducted his Ph.D. research on Nazism in the early 1970s, he was explicitly advised against pursuing Holocaust topics by senior faculty at the University of Wisconsin, with the suggestion that there would be "no future" in such work. More tellingly, when Browning later revealed that Holocaust perpetrators included ordinary, middle-aged family men—not predominantly Hitler Youth members or fanatical Nazis—his findings disturbed the Western Christian societies’ imagination that the Holocaust represented a break with Christian civilization, rather than a manifestation of its deepest traditions.

Historian David L. Bergen, in her Cambridge study on Catholics, Protestants, and Christian Antisemitism in Nazi Germany, documents how "recent trends in the study of National Socialism tend to downplay the significance of antisemitism—in particular of Christian antisemitism—in producing the Holocaust". Yet Bergen also notes that Donald Niewyk's earlier analysis of pre-Nazi German antisemitism demonstrates that "the old antisemitism had created a climate in which the 'new' antisemitism was, at the very least, acceptable to millions of Germans".

In other words, Western scholars were consciously choosing to deemphasize the role of Christian theology and practice in making the Holocaust comprehensible and tolerable to millions of perpetrators and bystanders.

After 1945, both Protestant and Catholic Church leadership engaged in what might be called "denazification mythology." As Ericksen documents, this involved:

- Centering marginal voices: Scholars focused narratives almost entirely on individual heroes like Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Martin Niemöller, while systematically suppressing evidence of widespread Christian enthusiasm for Hitler

- Redefining resistance: The Confessing Church's opposition to the pro-Nazi Deutsche Christen was reframed as anti-Nazi resistance, when in fact it was an inner-church theological struggle that many Nazis could fully support (indeed, Wolfgang Gerlach's authoritative study found that antisemitism in the Confessing Church rivaled that of the Deutsche Christen)

- Erasing uncomfortable figures: Theologians like Emanuel Hirsch, Paul Althaus, and Gerhard Kittel—who enthusiastically merged Christian anti-Judaism with Nazi racial antisemitism—were deliberately removed from postwar scholarship and institutional memory

Notably, when scholar Ernst-Wolfgang Böckenförde exposed the Catholic Centre Party's enabling of Hitler in 1933 and documented Catholic enthusiasm for Nazi ideology, he was denounced as "patently unserious" and his methods described as "extraordinarily primitive" by his peers. This was not a scholarly disagreement—it was institutional gatekeeping designed to protect the Church's post-war reputation.

By conflating the swastika with the Hakenkreuz, Western academia could avoid the following inconvenient historical facts:

- The Christian Church's 2,000-year tradition of antisemitism directly enabled the Holocaust—not as aberration, but as culmination

- The Hakenkreuz had Christian, not Hindu, origins—rooted in the medieval gammadion cross and the ecclesiastical symbolism that saturated Hitler's formative years

- Christian leaders and institutions were not victims but collaborators—the Centre Party enabled dictatorship, bishops swore loyalty oaths, and clergy participated enthusiastically in Nazi ideology

- The very structure of Christian supersessionist theology made the Holocaust conceivable—as theologian John Dominic Crossan noted, "without Christian anti-Judaism, lethal and genocidal European antisemitism would have been impossible or at least not widely successful"

Raul Hilberg, the foundational Holocaust historian whose massive 1961 work “The Destruction of the European Jews”, documented the systematic genocide explicitly connected Nazi antisemitism to Christian traditions. Hilberg showed that "Christian antisemitism is the basis of racial antisemitism". Yet, despite this foundational insight, subsequent generations of scholars downplayed rather than amplified this connection.

Conclusion

From the above it is crystal clear that the Nazi Hakenkreuz has no connections whatsoever to the Hindu Swastika, and was inspired by Christian iconography and ideals dating to the time of the Roman Empire.

The Gammadion, better known as the Crux Gammata, installed in the Lambach Abbey by Theodorich Hagn and observed by Adolf Hitler during his days as a choirboy served as the inspiration for the Nazi Hakenkreuz.

Yet, in an effort to cover up the Christian ideals that inspired Nazi anti-semitism, Western historians have misconstrued the Hakenkreuz as a Swastika in an attempt to divert blame from the Church’s involvement with Hitler and direct it to Indic faith.

It is high time this grave error of history is recognised by all concerned and a movement brought forth in order to recognise the Hakenkreuz for what it is - a Christian symbol adopted by Nazis for their sinister purposes of anti-Semitism and hatred.

Sources :

- britannica.com - Swastika | Description & Images https://www.britannica.com/topic/swastika

- historyextra.com - Why did Hitler choose the swastika as a Nazi symbol?https://www.historyextra.com/period/second-world-war/why-did-hitler-choose-the-swastika-as-a-nazi-symbol/

- britannica.com - How the Symbolism of the Swastika Was Ruined https://www.britannica.com/question/how-the-symbolism-of-the-swastika-was-ruined

- liturgicalartsjournal.com - Gammadiae: The Mysterious Lettered Symbols Depicted on Early Christian Frescoes https://liturgicalartsjournal.com/gammadiae-the-mysterious-lettered-symbols-depicted-on-early-christian-frescoes/

- sacred-texts.com - The Migration of Symbols: Chapter II. On the Gammadion or Fylfot https://www.sacred-texts.com/eso/mos/mos05.htm

- gracefiber.com - Byzantine Cross: Origins, Symbolism & Historical Significance https://gracefiber.com/byzantine-cross-origins-symbolism-historical-significance/

- britannica.com - Cross | Christianity, Symbolism, Types, & History https://www.britannica.com/topic/cross-symbol

- dergipark.org.tr - THE CROSS IN BYZANTINE ART: ICONOGRAPHY AND THEOLOGY https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/ejophs/issue/43866/532854

- britannica.com - Mein Kampf | Quotes, Summary, Banned, & Analysis https://www.britannica.com/topic/Mein-Kampf

- harvard.edu (Nuremberg) - Extracts from Mein Kampf, on the need for living space https://nuremberg.law.harvard.edu/

- openlibrary.org - Hitler by Werner Maser https://openlibrary.org/works/OL2827319W/Hitler

- goodreads.com - Hitler: Legend, Myth and Reality by Werner Maser https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/2836370-hitler

- archive.org - Hitler's letters and notes : Maser, Werner, 1922-2007 https://archive.org/details/hitlerlettersand0000mase

- archive.org - Mein Kampf : Hitler, Adolf, 1889-1945 : Free Download https://archive.org/details/MeinKampf_201509

- countercurrents.org - Holy Hatred: How Nazi Propaganda Exploited Christian Anti-Semitic Myths https://countercurrents.org/2025/02/holy-hatred-how-nazi-propaganda-exploited-christian-anti-semitic-myths/

- cambridge.org - Catholics, Protestants, and Christian Antisemitism in Nazi Germany https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/central-european-history/article/catholics-protestants-and-christian-antisemitism-in-nazi-germany/

- cambridge.org - Christianity and Anti-Semitic Propaganda in Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/comparative-studies-in-society-and-history/article/in-the-name-of-the-cross-christianity-and-antisemitic-propaganda-in-nazi-germany-and-fascist-italy/

- encyclopedia.ushmm.org - Antisemitism | Holocaust Encyclopedia https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/antisemitism

- encyclopedia.ushmm.org - The German Churches and the Nazi State https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-german-churches-and-the-nazi-state

- concordatwatch.eu - Reichskonkordat (1933): Full text https://www.concordatwatch.eu/Concordat-between-the-Holy-See-and-the-German-Reich.html

- americamagazine.org - The Vatican Concordat With Hitler's Reich https://www.americamagazine.org/faith/2003/08/31/vatican-concordat-hitlers-reich

- catholicnewsagency.com - Hitler, the Holy See, and a historic treaty https://www.catholicnewsagency.com/news/42394/hitler-the-holy-see-and-a-historic-treaty

- facinghistory.org - Hitler's Agreement with the Catholic Church https://www.facinghistory.org/resource/hitler%E2%80%99s-agreement-catholic-church

- aeon.co - How Nazism ended centuries of Catholic-Protestant enmity https://aeon.co/essays/why-has-the-role-of-catholicism-in-nazi-germany-been-so-long-ignored

- encyclopedia.ushmm.org - The Enabling Act of 1933 | Holocaust Encyclopedia https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-enabling-act-of-1933

- bundestag.de - The Enabling Act of 23 March 1933: The political situation in the German Parliament https://www.bundestag.de/

- theholocaustexplained.org - How did the Nazi consolidate their power? https://www.theholocaustexplained.org/en/beginnings-of-genocide/the-period-of-genocide/how-did-the-nazis-consolidate-their-power/

- spartacus-educational.com - Michael von Faulhaber https://www.spartacus-educational.com/GERfaulhaber.html

- concordatwatch.eu - Von Papen, papal chamberlain and Nazi negotiator https://www.concordatwatch.eu/Von-Papen-papal-chamberlain-and-Nazi-negotiator.html

- jewishvirtuallibrary.org - Nuremberg Trial Defendants: Franz Von Papen https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/franz-von-papen

- time.com - Foreign News: Concordat https://time.com/

- facinghistory.org - Christian Churches and Antisemitism: New Teachings https://www.facinghistory.org/resource/christian-churches-and-antisemitism-new-teachings

- pdfs.semanticscholar.org - Religion as Hatred: Antisemitism as a Case Study https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/

- academia.edu - (PDF) Christianity, Antisemitism, and the Holocaust https://www.academia.edu/

- uvm.edu - German Churches and the Holocaust https://www.uvm.edu/

- commentary.org - Christianity and the Holocaust https://www.commentarymagazine.com/articles/christianity-and-the-holocaust/

- journals.sagepub.com - Revisiting Bonhoeffer and the Jews - Mark Braverman, 2022 https://journals.sagepub.com/

- digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu - The Orthodox Betrayal: How German Christians Embraced Nazi Ideology https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/

- jguaa2.journals.ekb.eg - The Concept and Utilization of Swastika "Hooked Cross" on Textiles https://jguaa2.journals.ekb.eg/

- wisdomlib.org - Harivamsha, Hari-vamsha, Harivaṃśa, Harivamsa https://www.wisdomlib.org/

- vedavidhya.com - Swastika (卐) Symbol in Hinduism https://www.vedavidhya.com/swastika-symbol-in-hinduism/

- fiav.org - The Ancient Symbol of Swastika: Its Distortion, Uses and Misuse https://www.fiav.org/

- gutenberg.org - A PROSE ENGLISH TRANSLATION OF HARIVAMSHA https://www.gutenberg.org/

- practicalsanskrit.com - The misunderstood Swastika https://blog.practicalsanskrit.com/swastika/