The Business of Faith: Investigating the Economics of Halal Certification

Imagine sitting down to order your favourite meal at your beloved restaurant. You take in the smells and the sounds, mouth watering while waiting for the arrival of your comfort food. And then, it finally arrives. Just taking in the aroma of the hot fare makes you feel better already.

You slowly savour the exquisite flavours, enjoying the cuisine on offer. By the end of your culinary sojourn, you leave the bistro with a deep sense of satisfaction and fulfillment. After all, what experience is better than that of having one’s fill of good food and drink?

Imagine the shock and sheer horror on your face if someone told you that the lip-smacking meal you just had provided the funds for an insidious organisation that helps terrorists evade the hand of justice and organises violent and illegal protests against the government.

Now, you may think this sounds like a conspiracy theory with no basis in reality. After all, how could a reputed establishment knowingly and willingly fund paralegal activities?

But what if the establishments do not realise the impact of their actions, and how they still directly fund the operations of one of the most sinister Islamic organisations to grace our country?

Read on to uncover how the food industry in India is under the thrall of radical Islamists and how Hindus have unwittingly sponsored their own doom for almost half a century now. Uncover the deepest and darkest secrets of the halal economy in India and around the world, and how it impacts you directly in the comfort of your home.

Exploring the Islamic concept of Halal

Now, a burning question occupying our minds is : What is Halal?

Roughly speaking, halal can be defined as that which is permissible, allowed, sanctioned or legal by Sharia law for Muslims.

Halal is discussed in the Quran most notably in verse 5:3, which states the following : "Forbidden to you are carrion, blood, and swine; what is slaughtered in the name of any other than Allah; what is killed by strangling, beating, a fall, or by being gored to death; what is partly eaten by a predator unless you slaughter it; and what is sacrificed on altars. You are also forbidden to draw lots for decisions. This is all evil. Today the disbelievers have given up all hope of undermining your faith. So do not fear them; fear Me! Today I have perfected your faith for you, completed My favour upon you, and chosen Islam as your way. But whoever is compelled by extreme hunger—not intending to sin—then surely Allah is All-Forgiving, Most Merciful."

It is also further discussed in Hadiths like Sahih al Bukhari (2057), and Sahih Muslim (1966).

The above verses provide a broad outlook on what is considered permissible by Muslims for consumption.

Almost all domestic animals are considered halal for Muslims to consume, with the exceptions of pigs and dogs.

Apart from them carnivores, scavengers and omnivores (amongst both birds and mammals) are also considered haram and unfit for consumption.

These are considered haram, which is also the antonym of halal. It can roughly be translated to mean “forbidden”.

But is it enough for an animal to be considered halal and fit for consumption if it ticks the above boxes?

About Halal slaughter

Another interesting criteria concerning Halal is that it is not enough for an animal to meet the above requests to be considered fit for consumption - it must also be slaughtered in a manner peculiar to Muslims.

What is this criteria?

Firstly, a non-muslim cannot participate in the slaughter of the animal. Doing so disqualifies the meat from consumption by devout Muslims.

Secondly, the ritual Islamic prayer of Zabiha must be recited to the animal before its slaughter.

The slaughter must follow the pattern of a ventral cut with multiple strokes without lifting the knife at the throat, severing the trachea, oesophagus and other vital blood vessels.

Here is the most fascinating part - according to Islamic jurisprudence, once an animal is slaughtered, its blood is termed najis, i.e filthy. Therefore the animal must be completely drained of its blood to be deemed halal and fit for consumption.

Not to mention the spinal cord is to be left completely intact and untouched during the entire process.

In other words, the animal that is to be slaughtered in order to make halal meat is bled out to death - and it can feel every single second of the pain, since its spinal cord is left untouched by the executioner.

If you thought the animal could be stunned to ease its suffering, think again - as the Prophet of Allah clearly mentions that it is haram to partake of that which is beaten to death. This encompasses stunning as well.

Notwithstanding the legal and humanitarian aspects that cloud halal meat - it is required by law in India for an animal that is to be slaughtered to be stunned - there are deeper economic consequences related to the practice of halal, consequences that are in fact deeply tied to certain political machinations grinding away in our nation.

Halal Economy - An Overview

The obvious next question is regarding how Halal as a practice has been commodified, and in turn has given birth to an economy of its own. And how you, as consumer, are unknowingly sponsoring an ecosystem that works to fund paralegal protests and the freedom of known terrorist sympathisers in our own soil.

The major certifier for halal food in India is the Jamiat Ulema i-Hind Halal trust, which is a wing of the Jamiat Ulema i-Hind. For a restaurant to be certified as serving halal meat, they must procure their meat from a facility certified by the trust.

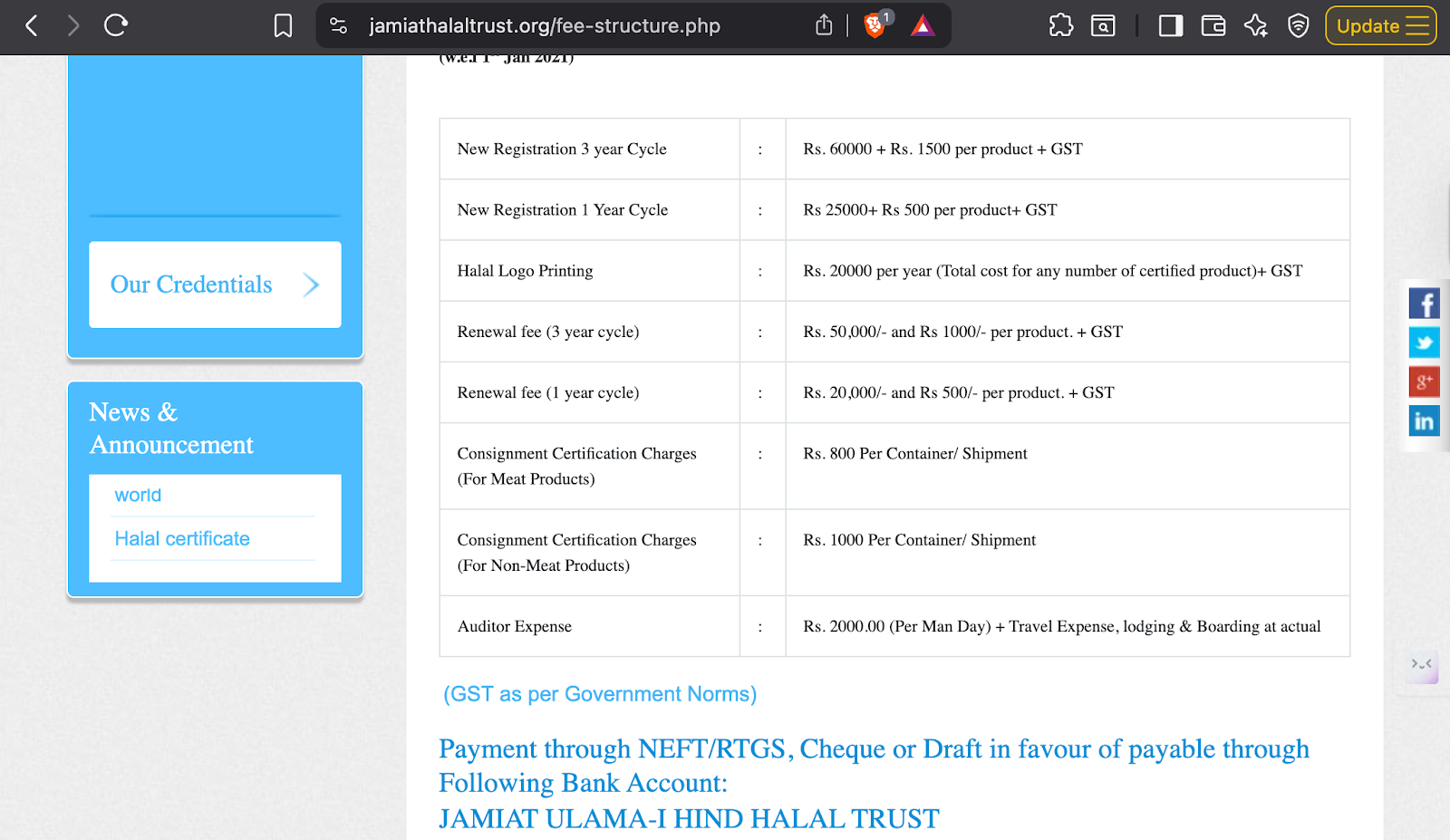

And what are the associated costs for obtaining such a certificate, you may ask?

Above is the fee structure of obtaining halal certification, as per the official website of the Jamiat Ulama i-Hind Halal trust.

From the above table, we can safely say it takes around INR 50,000 for a single unit of a meat processing facility to be deemed halal.

The halal economy in India is estimated to be worth around 285 million USD (and still growing), of which a major chunk is represented by the costs of obtaining this certification.

So where does all this money obtained from certification go to?

How the Halal Economy Funds Extremism

The Jamiat Ulema i-Hind Halal Trust is a wing of the parent organization known as the Jamiat Ulema i-Hind, which represents Muslims belonging to the Deobandi sect of Sunni Muslims. While they style themselves as an organization championing the rights of Indian Muslims, here’s a deeper examination of their actions that reveals more about the nature of the Jamiat.

The 8th of February, 2022. The courts finally give a verdict on the case of the 2008 Ahmedabad bomb blasts that claimed the life of 56 and injured another 200. The death penalty is awarded to 38 of the conspirators.

But within hours after the special court announced the death penalty to them and granted life imprisonment to 11 others for their roles in the tragedy, the Jamiat Ulema-e Hind rejected the verdict saying that the decision of the special court is unbelievable.

To quote Maulana Arshad Madani, the President of Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind, ““the decision of the special court is unbelievable, we will go to the High Court against the punishment and continue the legal battle”.

Maulana Madani stated that the country’s top lawyers would fight tooth and nail to protect the criminals from being hanged. “We are confident that the High Court will deliver complete justice to these individuals,” said the Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind chief.

Now, you might think that this case is a one-off, and the Jamiat truly thought they were saving the lives of innocent men condemned to the gallows by a corrupt court.

Yet this is not the first time this has happened.

The very first cases the Jamiat took up were the 7/11 Mumbai train blasts, the 2006 Malegaon blasts and the Aurangabad arms case.

Not to mention that the Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind had also defended the accused in the 26/11 Mumbai terror attacks case, the 2011 Mumbai triple blasts case, Mulund blast case and Gateway of India blasts case!

In 2013, Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind had provided free legal aid to Indian Mujahedeen terrorist Mirza Himayat Baig, who was accused in the German Bakery bomb blast case. The Indian Mujahideen terrorist was sentenced to death by a Pune court on April 18, 2013, along with co-accused Yasin Bhatkal.

The Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind has actively provided legal assistance in a number of high-profile cases where individuals were accused of involvement in terrorism-related activities. Among the cases in which the organization extended legal or financial aid are the Lashkar-e-Taiba connection case (Abdul Rahman v. State SLP), several ISIS-related conspiracy cases in Kochi, Mumbai, and Rajasthan, the 26/11 Mumbai attacks (Syed Zabiuddin v. State of Maharashtra), the Chinnaswamy Stadium and Jungli Maharaj Road Pune bomb blast cases, multiple Indian Mujahideen and SIMI conspiracy cases, the Zaveri Bazaar serial blasts, the Jama Masjid blast, and the Ahmedabad serial blast case involving Yasin Bhatkal and others.

In addition, the group made headlines for its legal support to the accused in the assassination of Hindu leader Kamlesh Tiwari, with Jamiat’s leadership explicitly stating their willingness to cover all legal expenses and assigning the head of their legal cell to defend those charged in the case. This pattern of assistance demonstrates Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind’s consistent engagement in providing legal services to those accused in major criminal and terrorism cases, often framing their involvement as advocacy for fair trials and the legal rights of the accused.

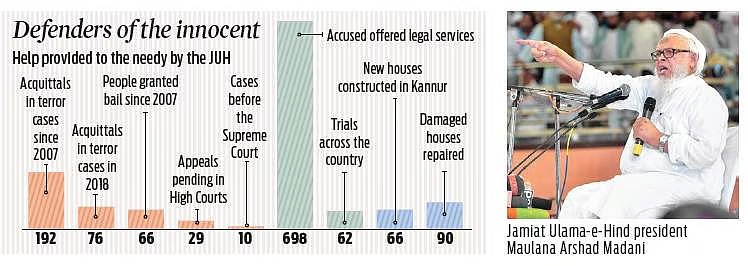

The above chart is a representation of the legal “services” offered by the Jamiat to the accused in terror cases !

So, if you were wondering where your hard-earned money spent on a well deserved meal went, this is what it sponsored. The legal fees of a terrorist attempting to evade justice.

Other Side Effects of the Halal Economy

While the halal economy in India drives significant growth in food production, exports, and consumer choice, it also raises concerns about economic exclusion and social inequities, particularly for non-Muslim communities traditionally involved in related trades.

The push for halal certification in meat processing and slaughter has been criticized for creating an informal "economic apartheid" by sidelining non-Muslims from key segments of the supply chain. Slaughterhouses and certification processes often prioritize halal-compliant facilities, where religious oversight by Muslim scholars or agencies is mandatory, effectively barring non-Muslim workers or owners from participating in certified operations. This exclusion stems from halal standards requiring adherence to Islamic rituals during slaughter, which can limit job opportunities and business access for others, leading to a segmented market where non-halal or mixed operations face reduced demand from certified buyers. In states like Uttar Pradesh and Maharashtra, where halal certification debates have intensified, regulators have even considered restrictions on non-halal slaughter to align with certification norms, further isolating non-compliant producers.

A contentious aspect is the flow of funds from non-Muslim consumers toward halal-certified products, which indirectly supports Islamic certification bodies and practices. With halal products now comprising a growing share of mainstream retail—estimated at 10-15% of the meat market in urban areas—purchases by Hindus and others contribute to revenues for certifying agencies like Jamiat Ulema-i-Hind Halal Trust, whose annual income exceeds Rs. 2 crore from fees and related services. Critics argue this creates a subsidy for Muslim religious infrastructure, as certification fees (e.g., Rs. 25,000-60,000 per registration plus per-product charges) and logo printing costs are built into product pricing, channeling everyday consumer spending into faith-specific validation processes without reciprocal benefits for other communities. This dynamic is seen as exacerbating inter-community economic divides, especially as non-halal alternatives become less viable in competitive markets.

Hindu communities engaged in butchery, swineherding, and allied animal husbandry, such as the Khatik (butchers), Valmiki (often involved in pig rearing and sanitation), and Vanavasis (tribal forest dwellers with livestock traditions), face disproportionate economic hardship from the halal economy's expansion. These groups, historically marginalized within the caste system, rely on non-halal meat processing for livelihoods, but the market shift toward certified halal meat—driven by exports worth over USD 4.4 billion annually—has eroded demand for their services and products. In regions like Rajasthan and Bihar, where these communities predominate, reports indicate job losses and income drops of 20-30% for small-scale butchers unable to afford or access halal certification, pushing many into informal or alternative low-wage work. Swineherding, already stigmatized, suffers further as pork is incompatible with halal standards, limiting integration into broader supply chains and perpetuating poverty cycles among Valmiki and Vanavasi groups, who comprise millions across rural India. Advocacy groups have called for inclusive policies to mitigate these effects, highlighting the need for government support in skill diversification for affected communities.

Conclusion :

The halal economy is not merely a religious framework governing dietary laws — it has evolved into an elaborate economic and ideological ecosystem that influences supply chains, market access, and even the flow of funds within our nation. What began as a matter of faith has quietly extended its reach into the financial and political spheres, often without the awareness or consent of the very consumers who sustain it.

For decades, ordinary citizens have unknowingly contributed to a parallel economic network that not only excludes non-Muslims from participation but, in some cases, has also been linked to institutions that actively defend individuals accused of anti-national activities. This is not an indictment of any faith or community, but a wake-up call to examine where our money goes, and what larger systems it sustains.

The need of the hour is not reactionary outrage, but informed awareness. Consumers must demand transparency in certification practices, and policymakers must ensure that economic systems remain free from religious monopolies or ideological capture. Only through vigilance and informed choice can we reclaim the economic balance that rightly belongs to all citizens — irrespective of creed.

Ultimately, it is not about boycotts or blame. It is about awakening — awakening to the quiet networks of power that shape our daily lives, and reclaiming the agency to decide what we consume, who benefits from it, and how it shapes the nation we leave behind.