The Passionate Muslims

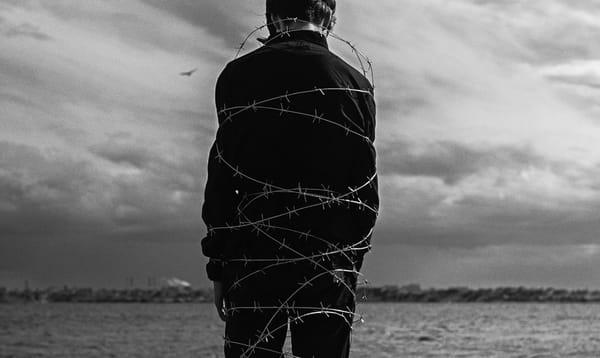

Why do subcontinental Muslims remain so restless, so perpetually aggrieved, even after getting exactly what they demanded? Pakistan was supposed to solve the Muslim problem. Two-nation theory, partition, separate homeland—problem solved, right? Except the problem didn't go away. If anything, it got worse.

The Muslims of the Indian subcontinent offer a very particular kind of passion, and it's worth understanding because it explains so much about why the region remains perpetually unsettled. It's not the passion of the oppressed fighting for freedom. It's the passion of people who got their freedom and discovered it wasn't what they wanted.

This passion manifests in three distinct but interconnected ways, each revealing deeper contradictions that partition was meant to resolve but ultimately amplified.

First, there's the passion of people who, despite Pakistan, still feel like a threatened minority.

Picture the absurdity: You create an entire country to solve the minority problem. You get your homeland. And then what happens? You spend your time obsessing over threats from India, America, Israel, and half the world besides.

From political rallies in Karachi to family discussions in Delhi, the same refrain echoes: we are under siege. Having Pakistan didn't cure this feeling—it made it worse. Now there are Muslims who "feel threatened" in India because they stayed (although their population keeps increasing at a healthy rate) and Muslims who feel threatened in Pakistan because the whole world is apparently conspiring against their new country.

The partition was supposed to end the anxiety but it actually multiplied it. It created two sets of insecure Muslims instead of one confident community.

But this passion of perpetual threat isn't really about external enemies. It's about internal doubt. When you build a country on the premise that you can't live with your neighbors, you never quite escape the suspicion that maybe you can't live with yourself either.

Second, there's the passion of people who view history as a pleasant tale of conquest but feel they've ceased to be conquerors.

The false narrative is everywhere—in textbooks, political speeches, cultural discourse. "The Mughals built the Taj Mahal. Muslims ruled India for a thousand years. We were the ones who brought civilization to the subcontinent."

But the truth is that the Muslims who ruled the region for a small portion of its long history had nothing to do with the majority of current subcontinental Muslims. Nothing. The Turks, Afghans, Persians, and Central Asians who invaded the subcontinent considered the local population najis—ritually impure. They didn't intermarry with locals by choice; they conquered them, converted them, often by force, and considered themselves a separate ruling class entirely.

Look at any Pakistani or Indian Muslim family. Check the DNA, examine the features, trace the actual lineage. The overwhelming majority are descended from local converts who were subjugated by the very Muslims they now claim as ancestors. It's the most perverse form of Stockholm syndrome in history: celebrating the people who tormented your actual ancestors and forced them to abandon their faith.

The passion here isn't just disappointed entitlement. It's the passion of people living in a complete historical fiction. When a Pakistani farmer claims Mughal heritage, he's claiming kinship with the people who would have considered his great-great-grandfather a third-class convert at best. When an Indian Muslim invokes the glory of the Delhi Sultanate, he's celebrating rulers who saw his bloodline as inferior.

But then the story goes off the rails even further. Because if you were such magnificent conquerors, how did you end up needing British bureaucrats to draw lines on a map to create your country? If you ruled for a thousand years, why did you need Mountbatten's calendar to tell you when you could be free? And most awkwardly: if you're really descended from conquerors, why do you look exactly like the people who were "conquered"?

This is the passion of people who remember being on top but were never actually on top. Pakistan was supposed to restore the "natural order"—Muslims ruling themselves again. Except the "natural order" was always locals being ruled by outsiders, and the current Muslims are the locals, not the outsiders.

Third, and this cuts deepest, there's the passion of Muslims who feel themselves on the margin of the true Muslim world.

Travel from Islamabad to Riyadh, from Dhaka to Cairo. Watch what happens when subcontinental Muslims meet Arabs. There's a particular energy—eager, defensive, slightly desperate to prove Islamic credentials. It's the passion of people who practice Islam with the intensity of converts but carry the anxiety of being seen as peripheral.

The Indian subcontinent was always the edge of the Islamic world, never the center. Islam came late, mixed with local traditions, created something that was authentically Islamic but not quite authentically Arab. The Muslims of the region know this, and Pakistan was supposed to fix it—create a pure Islamic state that could stand with the best of them.

Except it didn't work. Pakistani politicians still make pilgrimages to Washington before they make them to Mecca. Indian Muslims try to speak chaste Urdu to prove their Islamic sophistication. Bangladeshi religious movements still seem to be trying to out-Muslim everyone else. The passion of peripheral authenticity remained.

The cruel irony is that partition was meant to resolve these contradictions but instead crystallized them. The minority anxiety was supposed to disappear once Muslims had their own country. Instead, it split into different anxieties—Indian Muslims feeling more isolated, Pakistani Muslims feeling more embattled.

The historical nostalgia was supposed to be fulfilled by recreating Muslim rule. Instead, it created the impossible burden of living up to Mughal glory with twentieth-century bureaucracy—and the deeper impossibility of claiming inheritance from people who would have despised your bloodline.

The religious marginality was supposed to be solved by creating a pure Islamic state. Instead, it highlighted how difficult it is to be purely Islamic—genetically descended from the conquered rather than the conquerors, and psychologically trapped in a fantasy of ancestral glory that belongs to someone else entirely.

This is why the passion never dies down. It's not just about external circumstances—it's about internal contradictions that can't be resolved because they're based on historical lies. You can't cure an identity crisis built on claiming other people's achievements as your own heritage.

So what do you do with people whose problems weren't solved by getting exactly what they asked for?

If you're trying to understand the politics of the Indian Subcontinent, start here: Pakistan didn't cure Muslim passion—it relocated it. The fundamental discomfort, the sense of displacement, the feeling of being simultaneously too much and not enough—all of that remained.

If you're dealing with subcontinental Muslim communities, understand that their restlessness isn't about external oppression. It's about internal contradictions that partition was supposed to resolve but didn't.

And if you're wondering why the region remains so unstable decades after 1947, consider this: the passion that created Pakistan is the same passion that makes Pakistan impossible to satisfy. It's the passion of people who got what they wanted and are yet to discover that what they wanted was the wrong thing.

The most revealing thing about the Muslims of the Indian subcontinent is that they remain passionate about problems that their own solution was supposed to solve, while simultaneously celebrating the very people who created their ancestors' original problems. It's existential confusion dressed up as religious fervor, built on a foundation of historical fantasy that makes psychological peace impossible.