The unheard voice of forgotten exile

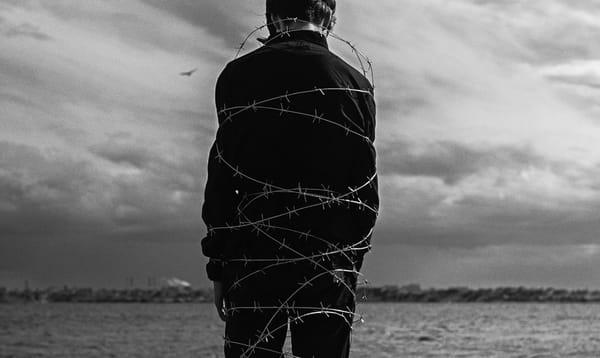

The Kashmiri Hindu genocide and exodus of 1990 easily remains one of India's most under-reported and under-acknowledged tragedies. The trauma of this tragedy haunts generations. And what's perhaps worse than the violence itself is how our story has been marginalized, politicized, pushed to the sidelines, and often deliberately erased from the mainstream discourse. Has this been accidental? Hardly.

History doesn't just happen. It gets written, edited, and sometimes, wiped clean. The media and academia, both powerful institutions that shape memory, have played their part in how this chapter has been remembered, distorted, or conveniently forgotten.

Lost In The Headlines

Media shapes public perception. And yet, despite the 1990 Kashmiri Hindu genocide leading to their exodus, it was underreported through a rather narrow political lens. Over 300,000 Kashmiri Hindus were driven out from their ancestral homeland overnight, fleeing threats, violence and unimaginable terror. It was a humanitarian crisis. But what did the media do?

The initial media coverage was sensationalist, completely missing the focus on the human cost of displacement and the suffering of Kashmiri Hindus altogether. The media houses, then and now, seem obsessed with pushing a one-sided 'secular' narrative. The idea of Hindus suffering wouldn't fit their narrative. Narratives of Muslim victimhood have often dominated, sidelining the brutal reality faced by Kashmiri Hindus.

What about cinema, the so-called 'soft power'? Cinema can be a very powerful tool for storytelling and shaping the public imagination. And yet, most films that touched upon Kashmir like Mission Kashmir, Haider, Shikara rarely ever focused on our experience. Where were the raw, unfiltered stories of what we went through? The loss, the fear, our uprooted lives? The portrayal was often more 'sanitized' and 'secular'. Our pain has either been invisible or diluted to keep the storytelling 'palatable'. The Kashmir Files was the one movie that came closest to showing our truth. It shook some people, even if it only scratched the surface of what we went through. But the backlash? It was instant. A whole crowd rushed to slap labels like "propaganda" or "myths" on it, dismissing our pain without a second thought. Worse, some so-called leaders mocked our suffering, turning the release of one film that dared to tell our story into a political circus.

The Missing Pages of History

Academia shapes policy and pedagogy. And yet, the Kashmiri Hindu genocide leading to their exodus remains conspicuously absent from school textbooks and university syllabi. It's 2025 and I still get blank stares or strange questions leading to the painful realization that the Kashmiri Hindu genocide is nothing but a ghost in India's textbooks and universities.

Ask any history student about what happened in 1990, you'll likely hear vague or worse, incorrect answers. Our school books talk at length about ancient empires, with chapters dedicated even to the Mughals but you won't find a mention of this piece of more recent history. As a result, the younger generations are much more unaware of the scale and implications of this tragedy and often have heartburn instead when the internet in the valley is shut down for security reasons.

There is no shortage of academic work on the broader Kashmir conflict - counter-insurgency, geopolitics, human rights violations. But the Kashmiri Hindu genocide? It's been buried, rarely studied as a standalone case of ethnic cleansing. Scholars and students who try, often hit walls. I've personally heard of student researchers whose theses were rejected for 'focusing too much' on the suffering of Kashmiri Hindus. Does truth need to be presented with a balancing act?

Universities and other institutions today are more concerned about political correctness than the truth. And when that happens, policy, curriculum and public memory all suffer. An entire generation knows much more about the internet shutdowns in the Valley than the exodus that shattered our lives.

Justice Delayed - Justice Denied?

Judiciary is meant to be the last resort for justice. But for Kashmiri Hindus, it feels like our cries have echoed in silent courtrooms - stuck, delayed or lost in the system. It's 2025, and not a single person has been convicted for the mass killings, rapes and terror that drove an entire community from Kashmir in 1990. Not one.

Talk to a lawyer, an activist, even victims or survivors like me - you'll mostly see resignation, exhaustion. The petitions that were filed have been caught in procedural delays, some dismissed on technicalities, others perpetually deferred. It often feels like justice itself has been in exile.

In 2017, when the activist group Roots in Kashmir approached the Supreme Court seeking a fresh investigation into the killings of over 700 Kashmiri Hindus, the petition was dismissed. The reason? 'Too much time has passed'. But does time erase the truth? Or grief? Does the right to justice come with an expiry date?

More petitions followed, some asking for the 1990 horrors to be officially recognized as genocide. But so far, there has been little progress. There are no special task forces, no dedicated tribunals, and certainly no official recognition in the language of law.

It's not like there is no evidence. We have names, records, survivor testimonies. Yet the system hasn't yet found the momentum to act. Every legal attempt seems to get stalled by delays or tangled in red tape.

So who does our community turn to when neither the courts nor the commissions take our suffering seriously? In the absence of judicial acknowledgement, the crimes committed remain unofficial, almost invisible in the eyes of the law. Until the judiciary calls it what it was, our exile will continue to represent not just a humanitarian tragedy but a legal and moral failure too.

Filling the Gaps

With these institutions failing us, we have become our only option. Survivors and their families trying to preserve the memory somehow. We have become our own archivists. Oral histories, blogs, memoirs, articles, podcasts, YouTube videos, and books like Rahul Pandita's Our Moon Has Blood Clots capture the fear, loss, resilience and longing that no statistics or headlines will ever be able to convey. They serve not only as documentation but also as acts of resistance against erasure. Some smaller community groups, magazines etc. give space to poetry, fiction, and essays that to some extent have helped survivors walk a step towards processing their grief and reclaim their identity. Imperfect perhaps, but powerful and necessary.

Building Narratives To Shape Memory, Identity, and Policy

So where do we go from here? Will our story find a rightful place in the collective memory of our country? That depends on how we choose to remember, and how we choose to tell. The silence and distortion of our history are already fraying our identity.

When newsrooms avoid telling this story, and classrooms ignore it, it fades from the national consciousness. I am already seeing our younger generation not growing up with the truth, in fact, worse, believing distortions and leaning towards a more secular narrative.

Without a narrative, there is no policy. Without policy, there is no justice. Today, the Kashmir issue is used as a political tool, or as an argument for different sides of the political spectrum. But where are the policies for rehabilitation? For justice? For return? Currently the few symbolic nods we have received seem more like PR than being steps towards redressal.

We could learn from how the world documented and remembered the Holocaust - relentless in preserving memory and seeking justice. We are nowhere close. Too often, we're caught in someone else's version of the story, or worse, left to downplay our own history.

This is Your Story Too

The genocide and exodus of Kashmiri Hindus is not just a chapter in a history book but a story of resilience, identity and survival. We are at a tipping point now. If we don't confront the silence surrounding it, we risk losing more than just history, we risk losing ourselves.

So to the journalists, editors, filmmakers, educators and policymakers - tell our story. Not as propaganda. Not as politics. But as the raw truth.

To the survivors and our children - speak up. Keep writing. Keep remembering. Keep documenting.

And, to the readers, listeners, allies - support the telling. Share the stories. Participate. Help the cultural preservation efforts.

Because if we don't tell our own story — someone else will. And they most certainly will get it wrong.