The Christmas Tree Problem

The photos showed up in my WhatsApp last week. A friend visiting a meditation 'ashram' in the backwaters, except the guru wasn't Hindu—he was a Father Smith, saffron robes and all, teaching "Christian meditation" to a room full of cross-legged Indians seeking enlightenment.

Her message: "This feels wrong somehow."

My response: "Actually, this is exactly right."

Because for Christianity it's never been about purity. It's about absorption.

The Thing About Yule Trees

Picture this: You're a Roman bishop in 400 CE. Half your congregation still leaves wine offerings for household gods. The other half asks why Christ's birthday happens to fall on the exact same day as Sol Invictus celebrations.

You have three options. Option one: declare all local customs satanic and watch your church empty. Option two: ignore the obvious contradictions and look like an idiot. Option three: do what Christianity has always done.

Rebrand everything.

That Yule tree your Germanic converts won't give up? Perfect symbol of eternal life through Christ. Those fertility rites timed to spring equinox? Ideal framework for resurrection celebration. The shrine to Brigid where your Irish parishioners keep showing up? Easy—Saint Brigid of Kildare now lives there.

Same location. Same rituals. Same human needs being met. Different management.

Here's What Actually Happens

Step one: Identify where people already go for the sacred. The temples, the sacred groves, the crossroads where they leave offerings.

Step two: Show up nearby. Not to compete, but to provide an upgrade path.

Step three: Speak their spiritual language. If the local holy man wears white, you wear white. If Sanskrit carries religious authority, you learn Sanskrit. If meditation connects people to transcendence, you teach Christian meditation.

Step four: Don't replace their practices—fulfill them. The village goddess protects crops? Christ ensures eternal harvest. Ancestor spirits provide guidance? The Holy Spirit provides better guidance.

Step five: Wait one generation. The children who grow up seeing saffron-robed Christian swamis teaching Sanskrit prayers in churches built according to vastu principles don't see contradiction. They see Tuesday.

Take Christian saints for example: half of them used to be pagan gods.

Saint Christopher? Originally a dog-headed giant from local folklore. Saint Brigid? Celtic fire goddess with a new backstory. Saint Nicholas? Adapted from various winter gift-giving traditions across Northern Europe.

The pattern repeats everywhere Christianity took root. Local deity serves community need. Christianity arrives. Local deity gets saint status and slightly modified mythology. Everyone wins.

Except not everyone wins.

The Vanishing Act

Three generations later, nobody remembers that Saint Brigid was once Brighid of the Tuatha Dé Danann. The fire festival survives, but the fire goddess doesn't. The rituals remain, but the cosmology vanishes. The sacred sites stay sacred, but the sacred stories get rewritten.

This is how cultures die without seeming to die. Not through violence—though Christianity has never been shy about that either—but through something more surgical. Through being absorbed so completely that they forget they were ever anything else.

Ask a Mexican about their relationship with the land. They'll describe saints who protect specific mountains, specific rivers, specific fields—saints who sound remarkably like the Aztec earth deities their great-grandmothers prayed to, except now they have new names and new bosses.

The old gods don't disappear. They just get promoted to middle management in someone else's hierarchy.

What My Friend Saw…

So when my friend felt unsettled watching a Father Smith teach Sanskrit meditation techniques in saffron robes, she was witnessing something both ancient and ongoing. Not Christianity embracing other traditions—but Christianity digesting them.

Because appropriation isn't what happens when teenagers wear bindis to music festivals. That's just ignorance dressed up as fashion. Real appropriation is what happens when entire spiritual systems get absorbed, rebranded, and redistributed under new ownership.

The Christian ‘guru’ in saffron robes isn't preserving Hindu meditation practices. He's converting them. Those cross-legged Indians aren't learning about dharma and moksha and the cyclical nature of existence. They're learning ancient Indian techniques rewired to deliver Christian conclusions. And with that transition, something irreplaceable disappeared.

The Last Shaman Always Converts

Christianity doesn't destroy other religions. It devours them. Carefully. Systematically. Leaving behind the bones picked clean of their original spirit, reassembled into more familiar shapes.

It's still Happening

Right now, somewhere, a Christian missionary is learning traditional healing practices from a native. Not to preserve them, but to prove that Jesus was the true source of their power all along. Somewhere else, a megachurch is incorporating Aboriginal dreamtime concepts into their worship services, explaining how these ancient insights actually point toward biblical revelation.

In Rishikesh and Dharamshala, Western converts are learning meditation techniques that took millennia to develop, then returning home to teach "contemplative Christianity" that mysteriously resembles Hindu practices with different vocabulary.

What Dies

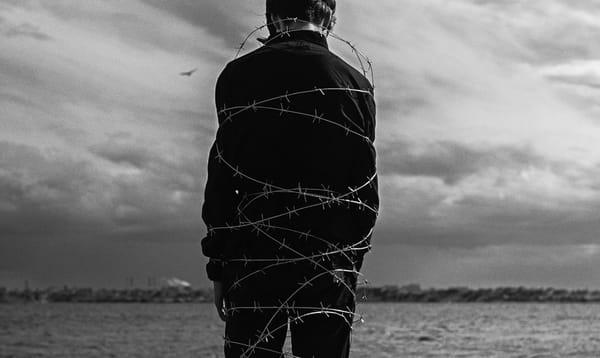

What dies is the chance for humanity to remember that there were other ways of being spiritual, other ways of relating to the sacred, other far more inclusive ways of organizing meaning.

When everything becomes Christian eventually, we lose the knowledge that other kinds of traditions were ever possible.

That's what my friend intuited in that WhatsApp message. That something was ending in that room full of cross-legged seekers. Another worldview completing its journey from sacred source to Christian resource.

Another culture finishing the long process of forgetting what it used to be.